Thirty years ago today, on July 9, 1979, the Voyager 2 spacecraft encountered Jupiter from a distance of 650,000 kilometers about its cloudtops, marking the second Voyager project flyby of the planet. The encounter provided an opportunity to see the anti-Jupiter hemispheres of Ganymede and Callisto, to monitor changes on Jupiter and Io since the Voyager 1 encounter four months earlier, and to observe Europa up close for the first time.

Thirty years ago today, on July 9, 1979, the Voyager 2 spacecraft encountered Jupiter from a distance of 650,000 kilometers about its cloudtops, marking the second Voyager project flyby of the planet. The encounter provided an opportunity to see the anti-Jupiter hemispheres of Ganymede and Callisto, to monitor changes on Jupiter and Io since the Voyager 1 encounter four months earlier, and to observe Europa up close for the first time.Back in March, we took an extensive look at the Voyager 1 encounter with Jupiter and Io. The Voyager 1 flyby provided a revolution in our understanding of the giant planet and turned the four Galilean satellites from mere points of light we were only beginning to understand into four separate worlds, each with their own unique geologies. In particular, during the Voyager 1 encounter, active volcanism was observed on Io as well as a narrow ring around Jupiter.

For Io, the second Voyager encounter did not provide the same revolution in our understanding of that world; the clear star of the July 9 encounter was the cracked world of Europa. While Voyager 1 flew within 20,000 kilometers of Io on March 5, 1979, Voyager 2's trajectory kept the spacecraft outside Europa's orbit and, with Io on the other side of Jupiter during closest approach, Voyager 2 never came close than 1,128,000 kilometers of Io. However, the discovery of active volcanism on Io by Voyager 1 necessitated a change in the schedule of observations for the second encounter, including a 8-hour long sequence of images of a narrowing crescent Io as Voyager 2 receded from Jupiter. This prolonged observation sequence allows Voyager 2 to monitor volcanic plumes along Io's limb, including those at Amirani, Maui, and Loki. From observations such as these, Voyager 2 found that most of the plumes first observed by Voyager 1 were still active during the July 1979 encounter. Only Pele appeared to have shut down, though later observations by Hubble, Galileo, and other spacecraft seem to suggest that the Pele plume is intermittently active. Volund was not observed near the limb of Io during the Voyager 2 encounter, so it could not be determined if that plume was still active.

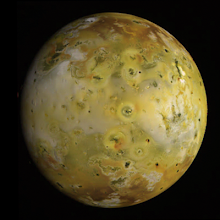

For Io, the second Voyager encounter did not provide the same revolution in our understanding of that world; the clear star of the July 9 encounter was the cracked world of Europa. While Voyager 1 flew within 20,000 kilometers of Io on March 5, 1979, Voyager 2's trajectory kept the spacecraft outside Europa's orbit and, with Io on the other side of Jupiter during closest approach, Voyager 2 never came close than 1,128,000 kilometers of Io. However, the discovery of active volcanism on Io by Voyager 1 necessitated a change in the schedule of observations for the second encounter, including a 8-hour long sequence of images of a narrowing crescent Io as Voyager 2 receded from Jupiter. This prolonged observation sequence allows Voyager 2 to monitor volcanic plumes along Io's limb, including those at Amirani, Maui, and Loki. From observations such as these, Voyager 2 found that most of the plumes first observed by Voyager 1 were still active during the July 1979 encounter. Only Pele appeared to have shut down, though later observations by Hubble, Galileo, and other spacecraft seem to suggest that the Pele plume is intermittently active. Volund was not observed near the limb of Io during the Voyager 2 encounter, so it could not be determined if that plume was still active. Earlier, Voyager 2 had observed Io while it was more illuminated by the Sun, like the image at left. The goal of these observation was to search for surface changes on Io as the result of volcanic activity between the two Voyager encounters. Among the changes observed were two new plume deposits surrounding Surt (probably active during a short, intense eruption in June 1979, but Surt was not viewed near the limb by Voyager 2 to see if it was still active) and Aten Patera. The presence of these changes from large plumes but without the observation of the plumes associated with them have led to the conclusion that large, Pele-type plumes tend to be short-lived compared to more persistent, smaller dust plumes like at Prometheus. Additional surface changes included a larger dark area within Loki Patera, the result of overturning of more surface area of the lava lake that covers much of Loki, and a change in the shape of the Pele plume deposit, from a heart shape to an oval. Subtle changes in the shape and intensity of the Pele plume deposit were also observed by Galileo in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Earlier, Voyager 2 had observed Io while it was more illuminated by the Sun, like the image at left. The goal of these observation was to search for surface changes on Io as the result of volcanic activity between the two Voyager encounters. Among the changes observed were two new plume deposits surrounding Surt (probably active during a short, intense eruption in June 1979, but Surt was not viewed near the limb by Voyager 2 to see if it was still active) and Aten Patera. The presence of these changes from large plumes but without the observation of the plumes associated with them have led to the conclusion that large, Pele-type plumes tend to be short-lived compared to more persistent, smaller dust plumes like at Prometheus. Additional surface changes included a larger dark area within Loki Patera, the result of overturning of more surface area of the lava lake that covers much of Loki, and a change in the shape of the Pele plume deposit, from a heart shape to an oval. Subtle changes in the shape and intensity of the Pele plume deposit were also observed by Galileo in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Of course, Io wasn't the only world Voyager 2 observed during its encounter 30 years ago. The star of the show was Europa. Europa was poorly observed during the previous Voyager encounter so this one really provided a great leap in our understanding of this icy world. Like Ganymede, Europa's surface was dominated by tectonic structures, ridges and dark, linear bands that criss-cross the surface. Unlike Ganymede, Europa's surface was found to be quite young with very few impact craters, though enough to show that the satellite's surface was much older than Io's. Spectral measurements suggesting a water ice surface, mass estimates between that of Io and Ganymede, and youth surface age soon led to the suggest that just beneath Europa's ice shell lay a liquid water ocean that today is a main focal point for exploration in the Jupiter system.

Of course, Io wasn't the only world Voyager 2 observed during its encounter 30 years ago. The star of the show was Europa. Europa was poorly observed during the previous Voyager encounter so this one really provided a great leap in our understanding of this icy world. Like Ganymede, Europa's surface was dominated by tectonic structures, ridges and dark, linear bands that criss-cross the surface. Unlike Ganymede, Europa's surface was found to be quite young with very few impact craters, though enough to show that the satellite's surface was much older than Io's. Spectral measurements suggesting a water ice surface, mass estimates between that of Io and Ganymede, and youth surface age soon led to the suggest that just beneath Europa's ice shell lay a liquid water ocean that today is a main focal point for exploration in the Jupiter system.Voyager 2 never got the same amount of attention that the earlier Voyager 1 encounter did. During the same week, Skylab was slowly approaching its destruction over Australia, dampening press interest in the encounter, along with the perception that this encounter was covering similar territory as the previous one. But Voyager 2 provided an opportunity to follow up on the discoveries made by Voyager 1 by allowing for an adjustment to the observation plan, such as to monitoring Io's volcanic plumes and Jupiter's narrow ring system as Voyager 2 receded from the giant planet. Voyager 2 also allowed imaging scientists to fill out the global map of Ganymede and Callisto by observing their anti-Jovian hemisphere and providing the first close-up look of Europa. The Voyager 2 encounter unfortunately also began a 17-year gap in close-up spacecraft imaging of the Jupiter system. But Voyager 2 went on to bigger and better things, including doing followup observations of the Saturn system in August 1981 as well as our only encounters of Uranus and Neptune in 1986 and 1989, respectively.

For this post, I have posted some movies on Youtube created in Celestia showing the geometry of this encounter:

- Voyager 2 Trajectory through the Jupiter System

- Animation of Io as seen from Voyager 2 in July 1979

- Animation of Io as seen from Voyager 2 in July 1979 - Short Version

No comments:

Post a Comment